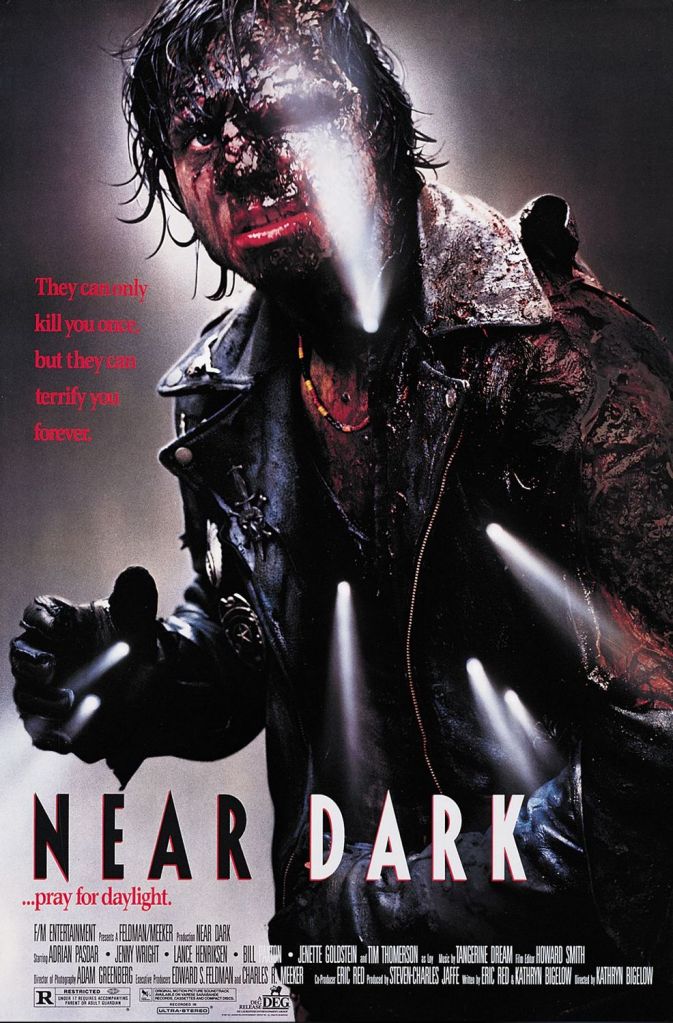

For all the glorious gifts it selflessly gave us, it’s still utterly unfathomable to me that ridiculously stylish vampire/western Near Dark isn’t as universally adored as other such genre mashing, 80s classics such as The Terminator or Predator. Not only did it finally bring some class to the merging of two such diametrically opposing concepts as bloodsuckers and cowboys after such staggeringly hokey attempts as Billy The Kid Versus Dracula, but it was the directorial debut of one Katherine Bigelow who would continue to go on to challenge classic movie tropes with such movies as Point Break and The Hurt Locker.

Not only that, but Near Dark also acts as a dream-like, gore soaked, revisionist Romeo and Juliet and even plays as an Aliens reunion as the trio of Lance Henriksen, Bill Paxton and Jenette Goldstein once again share the screen without the distraction of acid dripping xenomorphs cramping their style. So saddle up, cover the windows and prepare to witness arguably one of the most original vampire movies you’re ever likely to see.

Stetson wearing heart throb, Caleb Colton, is driving around the streets in a state of boredom, looking for something to hold his attention in the small, Podunk town where he lives, but he bites off more than he can chew when he catches the attention of doe-eyed drifter, Mae. They bond – as abnormally attractive people in these sorts of movies often do – but the twist in the tale of this union is that Mae is a vampire and Caleb is supposed to be her next meal. However, the vampire is fairly young and naive for an ageless bloodsucker and after biting her prey, she departs, leaving Caleb to turn as the sun starts to rise.

However, as Caleb starts to burn up as he flees for home, he’s scooped up by a mysterious RV with its windows taped over and comes face to face with Mae’s “family”, a clan of swaggering Nosferatu that’s made up of the steely-eyed Jesse, his predatory partner Diamondback, psycho redneck Severen and Homer, an old, bitter soul still trapped in the unaging body of a small child. Simply put, Jesse’s pissed that Mae has left such a gargantuan loose end flapping in the breeze and has an ultimatum for the terrified Caleb: join the family or die.

However, despite the allure of hanging with a devastatingly charismatic group of maniacs, Caleb is defiant about not taking a life, even though to resist ingesting innocent blood results in great pain. However, while Caleb is embarking on this nightmarish journey that’s one part Anne Rice to two parts David Lynch, his father and kid sister are searching for him after witnessing his abduction and when these two families finally meet, only disaster can follow. But while Jesse, Diamondback and Severen are quite happy to slaughter everyone and Mae is so torn, Homer fixates on Caleb’s young sibling, reasoning that if he was to turn her, he won’t be alone in his tragic/freakish predicament.

To dive right into the meat of the matter, surely the most accomplished thing about Bigelow’s direction is how many dueling themes she manages to balance that in lesser hands would most likely mix like water and oil and yet, miraculously, the sheer style of the piece locks everything together almost perfectly. The movie jumps from a mysterious romance that has the divorce from reality tone of a fairy tale, to creepy southern gothic, to a cool outlaw story, to a faustian tale all the while throwing in cool 80s gore and even the odd, kick ass bout of James Cameron-style action and it does it all without tonally missing a beat.

It’s frankly stunning and the secret is a visual language that mixes in a slick, noir feel that gives the night a glossy allure that’s just as seductive as Mae’s glassy eyes or Severen’s gleeful lack of respect with anything with a heartbeat. Sure, it’s so unrepentantly 80s, it makes Russell Mulcahy’s Highlander look like Kevin Smith’s Clerks in comparison, but there is an intelligence behind every back-lit crowd shot and dream-like haze.

It would have been easy to let the style override everything, yet while the romance between Adrian Pasdar’s Caleb and Jenny Wright’s Mae certainly plays into the realms of ethereal wish fulfillment, the clan of outlaw vampires feel very, very sharp and of the moment.

Discardingthe yearning glances that the lovebirds constantly throw each other’s way, the villains of the piece are violent, crass and oh so fucking cool with Lance Henriksen’s glaring patriarch utilising literally everything you love about the legendary character actor, be it his emaciated bone structure or his gravelly voice, but there’s a hinted-at, rich history to Jesse that’s only alluded to that makes him utterly fascinating, be it the claim that he started the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 or that he fought for the South during the American Civil War. Elsewhere, Jeanette Goldstein couldn’t be further from the iconic, masculine Vasquez from Aliens as she seductively slinks her way through the movie, every inch the woman to Mae’s wide-eyed waif. Adding a deeply creepy vibe is Joshua John Miller’s self loathing Homer who, despite being at least as old as the rest of the family, is still treated as the baby of the group which leads to his built up sexual frustration and his desire for Caleb’s sister takes the concept planted by Anne Rice to an unsettling degree. However, performing one of cinema’s most shameless acts of grand theft movie, is the late great Bill Paxton in the role of the maniacal Severen and for those only familiar with Paxton as a sniveling victim, his vulgar, whooping thug is an utter revelation. In fact, the two moments that see Near Dark operating at it’s full potential is the ones where the family takes complete control. While a later scene that sees the typical, Western shootout given a gothic spin as the vampires try to shoot their way out of a hotel room as pesky bullets cause far more lethal streams of daylight come cascading in, the moment where the group descend upon a redneck bar in order to feed is magnificent. As every member gets their chance to shine and Paxton pumps out wise cracks like a ruptured artery (“I hate it when they ain’t been shaved!” is a personal favourite), you genuinely want to belong to this band of murderous freaks, despite their nomadic, sordid existence.

Revisionist vampires came back in a big way during the mid-80s thanks to the likes of Fright Night and The Lost Boys, but for a turn that still feels fresh as the day it was released its symbiotic bonding with Western tropes (having no fangs, Severen at one point opens a man’s throat with his spurs) means that this is one vampire film that fittingly gets stronger as it gets older.

🌟🌟🌟🌟