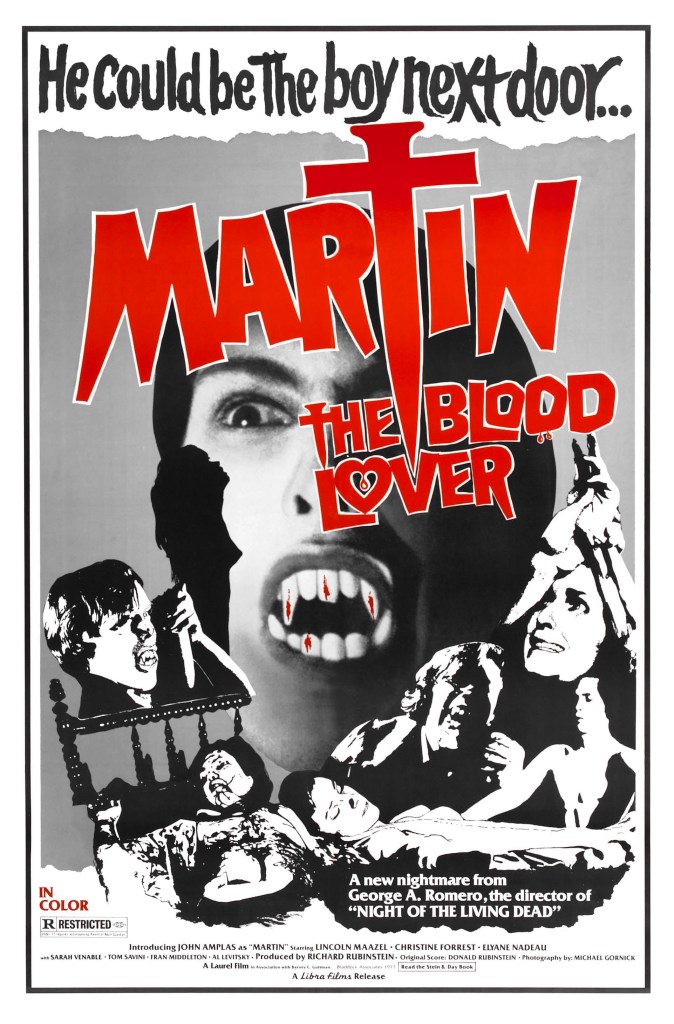

George A. Romero had already earned himself a reputation for adding an original spin on classic horror tropes thanks to his bold reinvention of the zombie myth (which he insisted on calling “ghouls”) with Night Of The Living Dead, but just before he managed to craft the absurdly influential Dawn Of The Dead, he turned his revisionist eye upon the vampire genre with arguably one of the most original musings the genre had ever seen.

In many ways, Martin is the ultimate anti-vampire movie as it takes all the usual tropes associated with endless Dracula movies and promptly stuffs them into the nearest trash receptacle in order to present to us a tragic and doom laden tale of mental illness, generational trauma and murder as we follow an incredibly messed-up young man as he attempts to make sense of his violent urgings through the veneer of that of a blood drinking Nosferatu.

We first meet the awkward and lonely Martin as he travels by train from Indianapolis to Pittsburgh in order to meet up with his elderly Lithuanian cousin Tateh Cuda and head onward to live with him in Pennsylvania, but instead of reading a book or catching forty winks, Martin spends the journey doing something inordinately more sinister. After some careful and intricate planning, Martin forces his way into a woman’s cabin and after struggle, sedates her, strips her and opens up her wrist with a razor blade in order to drink her blood.

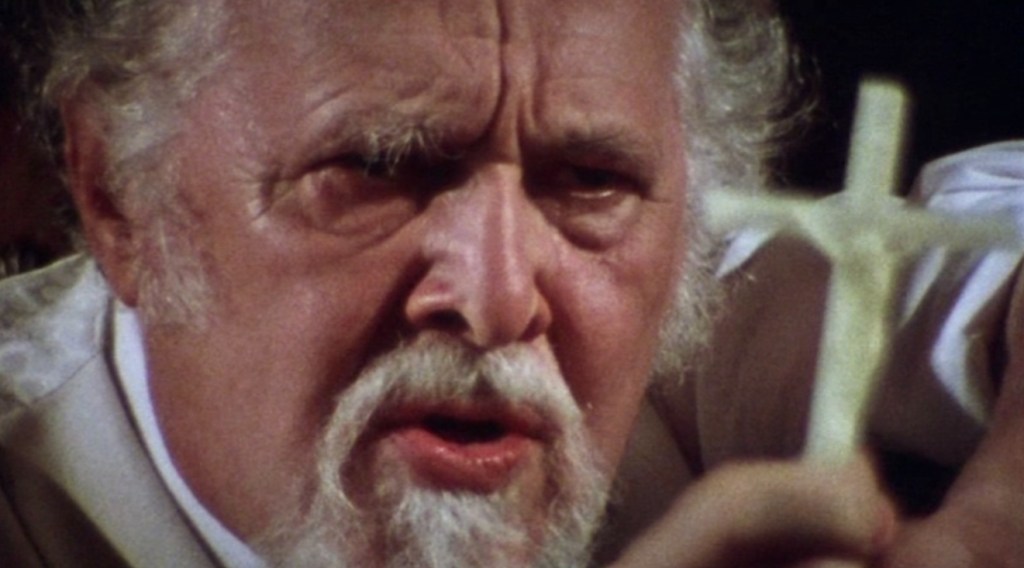

Yet Martin – for all of his murderous urges – is no simple mad-dog killer as his painstakingly planned and disturbingly gentle M.O. is the result of the delusion that the troubled youth genuinely believes himself to be a vampire. More tragic yet, after meeting up with Cuda, we find that this twisted belief is shared by his elderly cousin who, thanks to the superstitions and legends of the old country, truly believes that Martin is a supernatural being of evil. Once they arrive home, Cuda wastes no time constantly refurring to his cousin as “Nosferatu” and takes to brandishing crosses and garlic at the slightest whim, but appalled at his behavior is his granddaughter Christina, who has grown restless with her life and wishes to leave with her unreliable boyfriend, Arthur.

After getting a plain warning from Cuda that if anyone dies by his hand he’ll get a stake in the chest for his troubles, Martin starts plotting to claim his next victim while simultaneously building a bond with depressed housewife, Abby Santini, and finding a sounding board in the form of a radio talk show where the DJ labels him “The Count”.

As his urges build and build, Martin lust for blood letting builds, but if he gives in, what repercussions will follow?

Probably the most intelligent and thoughtful movie in Romero’s entire career, Martin boldly reinvents and reorganizes all the famous vampire lore into something approaching a nihilistic kitchen sink drama. Less a modern take on fangs and coffins, the movie is actually a contemporary take on mental illness in the young that paints Martin as just as much as a victim as the people he preys on, yet Romero delights in blurring the lines and muddying the waters as much as he can as the exact nature of Martin’s illness is kept as misty as the monochrome visions that our tragic lead is plagued by.

Romero never quite let’s us into what Martin’s flashbacks actually are; are they memories he believes come from his life as a Vampire or are they glamourised fantasies of what he believes is actually happening as they take the form of the classic Universal and Hammer movies that the director is so adroitly deconstructing? Yet while Martin has fully bought in to his murderous delusions, he still has some grasp on reality thanks to his constant attempts to convince Cuda of his humanity (“There is no magic.”) and the sharp intelligence he brings when stalking his victims.

Romero loads the film with foreshadowing, allegories and neat, unspoken touches that all push the movie toward its abrupt, inevitable conclusion. Despite all of his prep, none of Martin’s murders go quite the way he fantasizes as the beautiful, heaving blossomed and welcoming victims in his visions are replaced by a screaming woman in a blue face mask who engages her attacker in an awkward, decidedly realistic struggle. Elsewhere, Martin stalks a housewife when she is supposed to be alone only to find that she’s entertaining another man and thus has to desperately improvise in order to not get caught while still sating his thirst for the red stuff.

During some telling moments, it’s strongly hinted that some of Martin’s issues are due to issues with intimacy and sexual intercourse (which he tellingly abd childishly dismisses as “sexy time”) which causes troubles with his delusions when he’s approached by the tormented, middle-aged Abby, who’s advances causes him to be noticably off his game.

However, most tragic of all is the fact that Martin has received no help or understanding from anyone in his family, with outdated, old-world superstition leaving him and two other members of the family being ostracized and mistreated by embarrassed relatives that simply can’t understand that there’s merely a horribly confused child in front of them instead of a fanged beast. Only Christina offers any understanding or connection to Martin, but she also is stuck in an outdated life and has to abandon Martin in order to escape her claustrophobic existence.

It’s genius-level stuff and despite the obvious fact that Romero made this under extraordinarily limited means (he even appears as a trendy, modern priest), the script and acting surpasses the crude production with John Amplas virtually perfect in the emotionally complex lead role.

However, it’s the co-opting of the vampire legend to enforce our troubled lead’s fantasies that proves to offer up the most memorable and haunting visuals. The sight of Martin stalking through a house in a black turtle neck and carrying a hypodermic needle in his teeth is as potent a post-modern vision of vampirism as there’s ever been and he only takes on the appearance of a classic bloodsucker, complete with pallid face, plastic fangs and a dime store cape, when trying to drive home to his cousin that he is not a vampire – at not, a least not on the way he thinks.

Still, it all ends the only way it can, with a devastatingly ending so sudden, it leaves you feeling hollow and cheated that leaves leaves the players still stuck in their respective delusions or dead without ever receiving the understanding or help they unknowingly craved.

There were some grumbles at the time that Martin glamourized murder and that the movie even asked us to support him his delusions, but despite his crimes, Romero’s message is simple – Martin needed help and he just isn’t getting it from a world that refuses to loosen their death grip on the past.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟