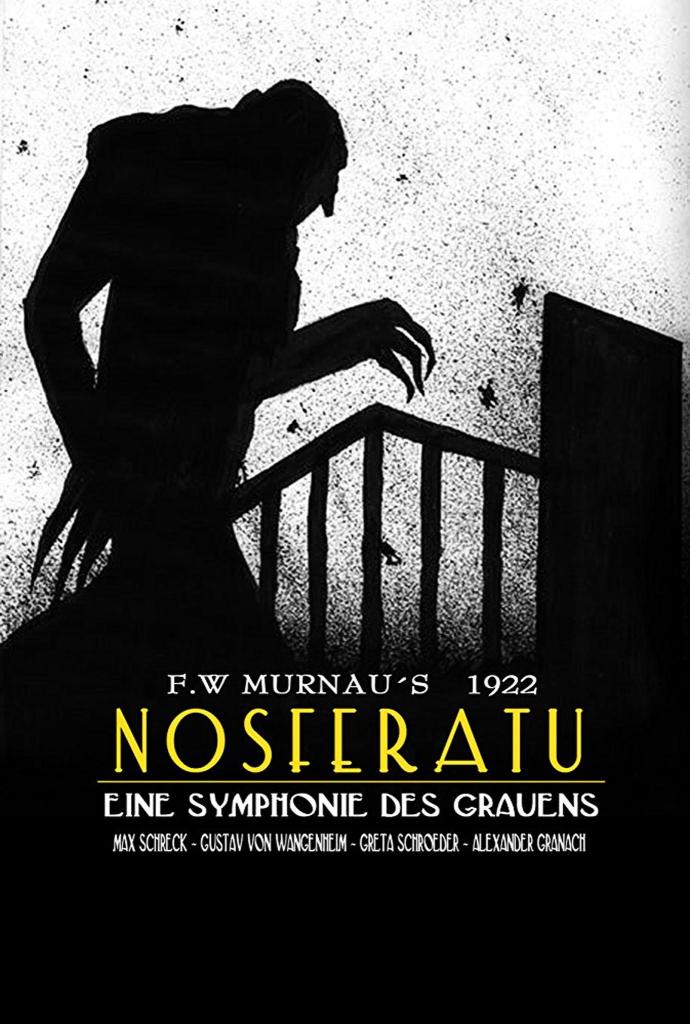

One of the things I love most about being a horror nut is the history, which means the further back you go, you can still plainly see themes and visual styles that still seem relevant today whether you go back twenty years, forty or even a hundred. Obviously, the most famous example of this is the great grandaddy of all scary movies is F.W. Murnau’s 1922 masterpiece of German expressionism, Nosferatu (or Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror to use its full title), a retelling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula that rejigged all the names about in order to play more German for German audiences. Predating all other famous incarnations of Stoker’s bloodsucker, the nightmarish Count Orlock created a visual language for a central, horror character that can be felt in every villain in a fear flick back through the ages be it the psychological effects of Freddy’s razor glove, to the stark appearance to the suited and booted Babadook – but even taking all that history into account, does a movie made over one hundred years ago still manage to hit the rights notes today?

Count on it.

The year is 1838 and estate agent William Hutter is sent from his German town of Wisborg all the way to Transylvania by his unscrupulous boss in order to sell some prime real estate in the area to a new client, the reclusive Count Orlock. However, after a long ride, Hutter finds that name dropping the Count’s name around the locals results in quite extreme reactions and the panicked staff of a local taven convince him not to make the final journey to Orlock’s castle after nightfall.

Still, he still has to get to his client sometime and almost right from the off, there seems to be something off about Orlock that goes far beyond being a rich eccentric. Discounting the Count’s rather freakish apperence, when Hutter cuts his thumb at dinner, Orlock makes a beeline for the wound in order to suck on it – something that goes far beyond just simple hosting, I’m sure you’d agree. However, upon waking the next morning, Hutter finds two puncture wounds on his neck which he foolishly attributes to a couple of mosquito bites and when Orlock admires a photo of his guests wife, Ellen, with a comment that she has a lovely neck, you really have to question Hutter’s survival instincts.

However, just when Hutter finally cottons on to what is happening, Orlock departs for Wisborg with three coffins full of dirt in tow, leaving the estate agent in his dust who realises that he’s going to have to try and race the Coubt home as he’s sold the vampire a house that is literally across the street from where he lives and where Ellen has been fretting about her missing husband.

As Orlock finally arrives in Germany, bringing death and plague in his wake, Hutter eventually arrives back to find his hometown suffocated under a cloud of fear, but it seems that the only thing that can stop the fearsome Orlock is a selfless sacrifice that the malformed Count simply can’t resist.

While it seems to be a rather obvious point to make, you really have to remember that you’re watching a movie that’s not only silent, but it comes from the infancy of cinema that requires a little bit of suspension of disbelief in order to navigate some of the story tropes that comes from a hundred year old German film. For a start, there’s many moments when you lose track of whether or not it is supposed to be day or night possibly because filming on location for a night shoot back in 1922 just simply wasn’t technically viable. As a result, there’s moments where some creepy shit is supposed to be occuring that just seems distractingly odd and the main culprit is a scene when Orlock, having just arrived at Wisborg, strolls cheerfully through a strangely deserted town with a full sized coffin under his arm in what seems to be a bright, sunny day. Elsewhere, there’s the usual amount of super exaggerated over reacting that comes part and parcel with the movie made in such an era, but if you can’t adjust your expectations for a move that was made a frickin’ century ago, then you just might want to stick with the Conjuring movies that might be more your speed.

However, while the story is a fairly faithful, if streamlined, retelling of Stoker’s seminal tale of terror – there’s barely any Van Helsing character and the movies version of Renfield goes into his insect eating mania without ever meeting his malevolent master – it’s those visuals and the presentation of its famous villain that really drives home how important this film is. Portrayed by the equally mysterious Max Schreck, Count Orlock’s long, shadowy reach can literally be felt all the way from kids films (Gargamel from The Smurfs and Goo from Despicable Me both seem to visit the same tailor) to direct homages that range from Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom to all the visual tricks employed by Francis Ford Coppola for his swing at Stoker’s novel. In fact, there’s a good chance that you’ve seen all of the visual treasure film has to offer even if you’ve never seen the film as these iconic moments slap down a blueprint that only an idiot would not think to follow.

While other incarnations of the Count choose to edge into the more charismatic, debonair areas on villainy, Orlock is a gnarled, clawed, repulsive cockroach of a creature, all gaunt and inhuman. Matching some boney, long-ass fingers with a pair of buck-toothed fangs that sit right at the front of his sneering mouth, he looks less like some hypnotic womaniser and more like a repellent parasite who spreads disease and sickness wherever he goes. However, while Schreck goes to town with his physical portrayal, Murnau matches him with some weird camera trickery that heightens that inhuman edge even further. The moment when Orlock rises from his coffin like his heels are hinged is probably one of the most famous horror image that exists and the fact that the Count can stretch his shadow ahead of him is truly chilling and can match anything made today in the eerieness stakes.

However, while that visual edge is what helped Nosferatu remain so memorable, there’s much more going on here than just some impossibly iconic shots and a monster for the ages. The final scene which sees Ellen taking matters into her own hands after a literal film full of fretting, sleepwalking and fainting and deciding to end matters once and for all by luring Orlock into a trap she’s spotted in a rather conveniently placed Nosferatu handbook. However, the fact that the movie reverses possibly one of the recognisable tropes in vampire history – the fanged beast feeding on a innocent in a white dress – before it was even a thing is nothing short of astounding. In fact, it’s the actual act of feasting on Ellen that proves to be the downfall of Orlock as he is so into the act, he doesn’t notice the sun creeping up behind him until it’s too late and while it’s a far more tragic end than some of the later, official versions of the story, it proves to be noticably more powerful than a standard stake through the chest.

Fittingly for a vampire film (arguably the vampire film), it blood continues to flow through the veins of modern horror a hundred years later and the creeping shadow of Nosferatu seems set to enshroud the genre for at least a hundred more.

🌟🌟🌟🌟

essential.

LikeLiked by 1 person