There comes a time when you watch an older film only to find, much to an incredibly surreal realisation, that you are undoubtedly watching something that went on to influence virtually everything that came after it. Some films feature an inventive use of cinematography that still feels overwhelmingly fresh to this day, with others it could be a tone, or even the way a particular character is presented that feels decades ahead of its time. Plot twists, endings, even an especially innovative film score can make you have a Gustav Graves moment of realisation mid-movie that you’re literally watching the language of cinema before your very eyes – but it takes an insanely capable masterpiece to change the game thanks to virtually every frame of its being.

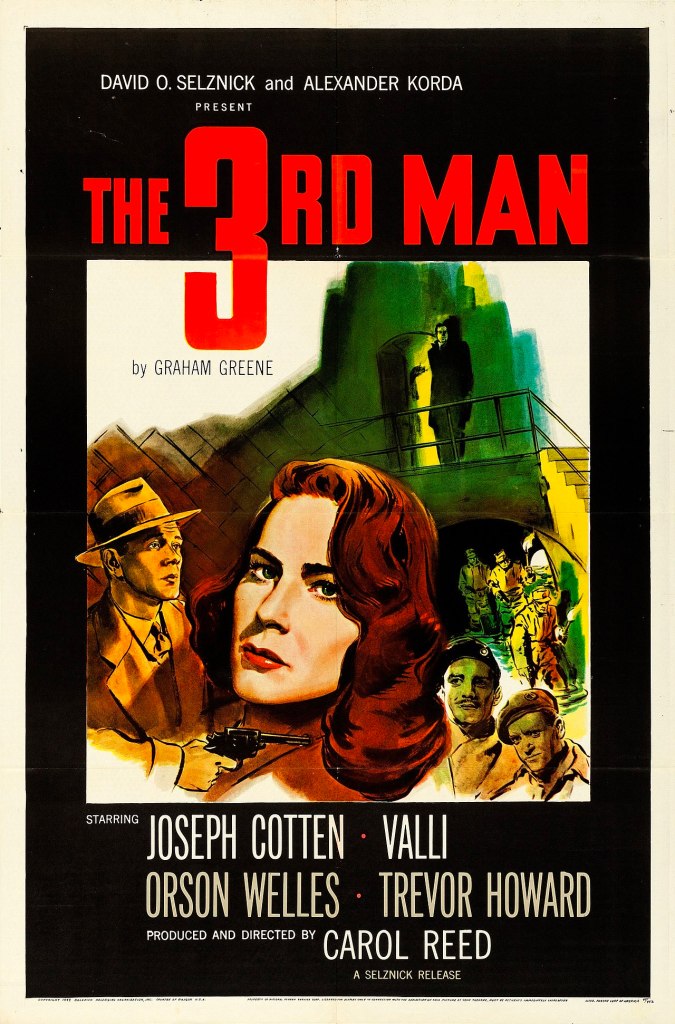

One such film is Carol Reed’s The Third Man, a movie that lurks in the darked doorway of greatness ready to bewitch you instantly with a shit-eating smirk – so cue that zither music and let’s get down to business.

Penniless pulp western author Holly Martins has arrived at the bombed out, scattered city of postwar Vienna in order to seek out his childhood buddy, Harry Lime, who has sent for him to offer him a job. However, upon arriving a Lime’s apartment, he’s greeted with some very startling news – his friend was literally killed just the other day after being hit by a passing vehicle while crossing the street. However, after attending Lime’s funeral, Holly soon starts to find that there’s aspects about his friend’s death that simply don’t add up and just like the entitled, American abroad he is, he starts his own, staggeringly clumsy, investigation into what actually happened.

Considering that the war has not only left large chunks of Vienna as piles of rubble, but divided into four seperate sectors each overseen by a different country (Soviet, French, British and American), Martins’ bumbling soon puts a few noses put of joint, with Major Calloway of the British sector in particular tutting in annoyance at the author’s flailings. But as he questions those known to be within Lime’s social circle, he soon finds himself drawn to Harry’s actress girlfriend, Anna Schmidt and their mutual love of the deceased soon helps them form a union which helps his inquiries greatly as Martins doesn’t even speak German.

However, as they’re driven by the fact that all the inconsistencies concerning the beloved Lime seems to be pointing at some sort of conspiracy, the scale of said plot is something that neither of them could ever hope to comprehend, especially when they’re informed that Harry racketeering gig was something far more sinister than forging the odd passport or selling the occasional crate of booze. However, when a sizable piece of the puzzle reveals itself, Martins has to wrestle with the knowledge that his good friend may not be anywhere near as good as he once thought.

There are many places to start when it comes to praising the twisty virtues of The Third Man, but I genuinely feel like I’d be doing the visuals of cinematographer Robert Krasker a gargantuan disservice if I didn’t address them first. Simply put, not only is this one handsome looking film, it maybe one of the most beautifully shot noirs I’ve ever seen as the movie evokes the topsy-turvy world of a bombed out Vienna through the stern, unsettling lens of German Expressionism as we’re left decidedly off-kilter with a succession of Dutch angles and harsh shadows that pump up the surrealism of Holly Martins’ partly self-inflicted plight. But in addition to this, way the light dances off the wet, cobbled streets mean that this may be the most hauntingly gorgeous looking, bombed city cinema has ever witness – certainly you’ve never seen a sewer look so impressive it could stand in for an ornate cathedral.

However, as stunning as the film looks even now, that’s not to say every other aspect of the flick isn’t absolutely top notch. In fact, you could suggest that The Third Man is some cruel, brutalist anti-version of Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca, that heartlessly strips out all the romance and nobility and leaves us in the company of some bitter, broken and viciously amoral people. Expectations are instantly confounded by Joseph Cotten’s Martins rather obnoxious hero who seems to think the world owes him some sort of explanation even if he doesn’t even truly understand the very questions he’s asking. Seemingly casting himself as one of the virtuous heroes of his own, cheesy cowboy novels, watching him fall bass ackwards should be an exercise in frustration, but there’s a certain mischievous glee in watching him try to crack a case that’s beyond him.

That case is, of course, the strange death of Harry Lime and its a shame that the film’s mid-story twist is so iconic, it’s practically common knowledge – but just on case you’re unfamiliar with it (you lucky bastard), get the Hell of this page and watch the film ASAP. For the rest of us, the shadowy reveal that Orson Welles’ charming, if utterly amoral, Harry Lime is actually alive and well after faking his death may be single greatest moment in film noir history. From there, Welles continues Harry’s criminal streak by promptly stealing the remainder of the film despite only showing up for a handful of scenes. Whether he’s explaining his chilling world view to a flabbergasted Holly on cinema’s most threatening ferris wheel ride, or fleeing for his life in an intense foot chase through the sewers (more like The Turd Man, amirite?), not only is he an utterly hypnotic as a man who has inspired utter devotion in his friends, but who manages to do all this while accompanied by Anton Karas’ insanely counterintuitive zither-based score. Not only does the strangely cheeful, plinky-plonky soundtrack add to the discombobulation (while evoking strange comparisons with Spongebob Squarepants), but it ingeniously sets it apart from virtually every other Noir movie ever made while the damn thing burrows into your subconscious like a particularly frenzied earworm. It takes a near-impossible combination of things to make the film remain unique after seventy five years (!), but the film also still carries an impressive emotional heft thanks to having us watch both Holly and Aida Valli’s grieving and political chess piece, Anna, have to weigh up the pros and cons of accepting what Harry is capable of.

Utterly immersive, amusingly impish and exceedingly tough to forget, Carol Reed’s monochrome ode to political culture shock and trying to break the bro code stands tall as one of the best noirs ever to play the game. And thanks to a razor sharp script, a determination to give a cheeky middle finger to a conventional happy ending and the sight of Orson Welles giving possibly the most charming/punchable smirks ever, you’d be a fool not to make The Third Man your first choice.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟