It may be a supremely callous thing to suggest, but even though the horror of the Vietnam war devastated an entire generation, split a country and took the lives of countless people as the conflict raged on, you can’t deny that it also some of the greatest accounts of gut punch cinema our species has ever witnessed. While the Second World War generally turned out heroic action thrillers in the 50s and 60s that praised the allies in their clearly defined battle against evil and the Gulf War produced sandy, tense dramas that frequently dived into the human condition, the Vietnam war on average delivered descents into sweltering, jungley Hell that saw the “good guys” fight not for their country or Capitalism, but often for their very souls against an identity sapping conflict.

All war films manage to do this to some extent, but there’s something about the surrealist trauma of ‘Nam that really let filmmakers cut loose, with such names as Francis Ford Coppola and Oliver Stone bringing their sensibilities to bare with stunning results. And yet, my favourite Vietnam film has always been Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket – a film that took the filmmaker’s cold, dispassionate, thousand yard stare style of cinema and delivered it to young men who eventually start giving it back.

A group of young recruits arrive at Parris Island in order to begin their basic training and join the Marine Corps and right away we start to see the individualism get stripped away from them as they are all given buzz cuts as they stare numbly into the mirror. However, this is kiddie pool compared to what awaits them as we then proceed to experience around fifty minutes of the most stressful cinema we’ve ever seen as drill instructor Gunnery Sergeant Gartman starts verbally picking them apart piece by piece with a string of humiliating insults that impact the self esteem harder that a rocket powered sledgehammer.

Through the duration of the training, we follow the smart mouthed Private “Joker” as he endures and thrives as he is moulded by Hartman’s abuse into a man who can kill for his country; however, bringing up the rear is the doughy Private “Pyle”, a hopeless, serial fuck up who attracts the scorn of his instructor and the hatred of his fellow trainees until something finally snaps.

A while later, we catch up with Joker based in Da Nang as a reporter for the newspaper Stars and Stripes and after weathering the Tet Offensive, he later is sent to Phu Bai to get a story where he meets up with Sergeant “Cowboy”, a man he trained with at Parris Island, and joins the unit known as “the Lusthog Squad” as they make their way towards what would be known as the Battle Of Huê. However, after losing their platoon leader, Cowboy is next in charge but inadvertently gets them lost in the city where they are soon targeted by a lone sniper. Earlier, Joker expressed a desire to finally experience the true warfare of Vietnam (or “The Shit” as it is bitterly referred to), but now that he’s gotten his wish, can he survive long enough to mull upon it?

While most Vietnam movies display the dehumanising effects of the war by having us trawl through what it was like dragging yourself through stinking jungle or watching soldiers ease the pain with drugs during their downtime, Full Metal Jacket does something rather different. You see in an attempt to see exactly what it takes to turn young, patriotic Americans into trained killers, Kubrick famously splits the movie into two parts with only the second hour devoted to Matthew Modine’s Private Joker finally seeing some real action after applying to be a military journalist, thus making Hartman’s angry Premonitions (“You’re not a writer, you’re a killer.”) ultimately come true. The first half is dedicated to seeing the emotional humanity grinder that is the training regime that’s become the more lauded and certainly more famous section of the movie. Simply put, it’s as perfect an hour of cinema as you’re ever likely to witness as Kubrick’s unwavering, unblinking and impassive eye holds on all the repetitive chants, marching and spectacular insults (I never realised how much of Hartman’s hideous, lightning fast, wit has actually managed to find its way into my day to day language) in order to perfectly put across how brutally effective grinding all this behaviour into a human psyche is – we go about a full twenty minutes before any line of dialogue isn’t screamed at a regimental volume. However, matching – and in many ways, surpassing – Kubrick’s meticulous vision is R. Lee Ermey’s frankly terrifying Hartman and his continued mental assault on Vincent D’Onofrio’s soft (in both mind and midsection) Private Pyle. In many ways, Ermey is the movie and when the film ultimately moves on from that midpoint time jump, some complain that the movie loses some of that laser intense focus that the flawless first half provides.

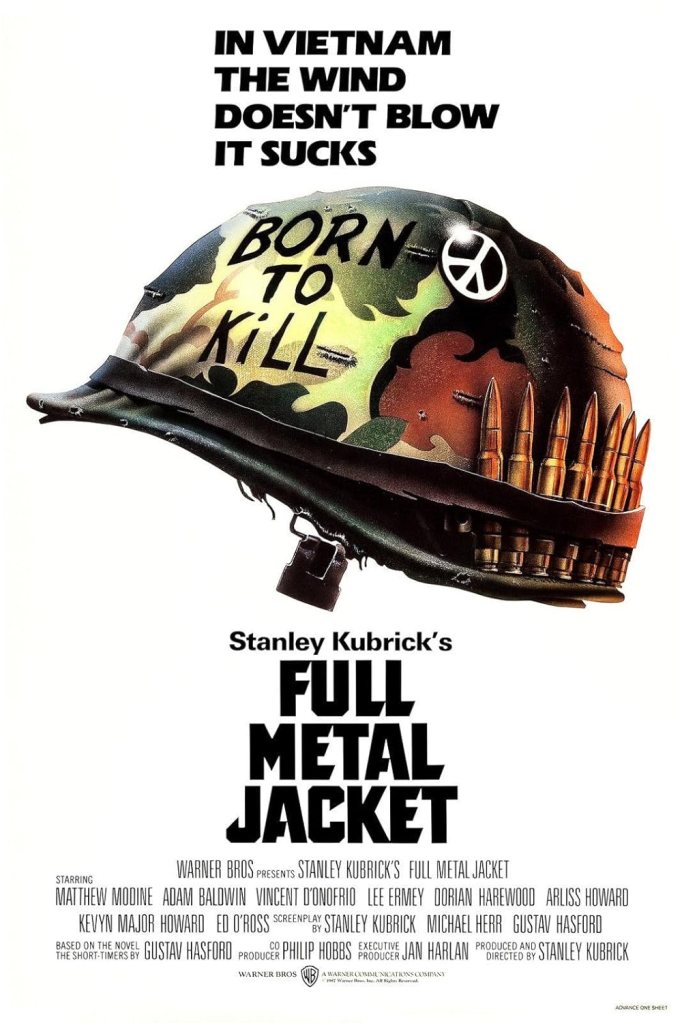

However, Kubrick is obviously condemning what it takes to break a human being down in order to make them fit for the fresh hells of war and is showing us that conflict is so harrowing that even preparing for it can fray the sanity to a lethal degree. In fact, Kubrick indulges in some pitch black humour by even having Hartman hold up like likes of Charles Whitman and Lee Harvey Oswald as exemplary examples of rifle work. But once we head over to Vietnam, all the rigid order we’ve been experiencing both literally and metaphorically, suddenly tumble away leaving our characters to chaotically stumble about. Joker, now a reporter, still wants to truly experience war despite his combative nature (he wears both a peace button and yet has “Born to kill” scrawled on his helmet), but after joining with Cowboy’s unit, soon sees him devoid of any true leadership. Worse yet, finding themselves lost, The Lusthog Squad wander into the sights of a lone sniper who picks off anyone who is able to give a coherent order leaving the rest to argue about how best to proceed.

With the terrible order of training replaced with the even worse feeling of chaos, valiant acts are performed by grown men who happily call themselves names like Animal Mother and Joker finally gets his opportunity to live up to the graffiti written in his head gear, but by then the rampant moral grey areas have enveloped us all like the acrid smoke that billows through the ruined buildings. It’s powerful stuff and it’s a wonderfully grey counterpoint to the phantasmagoric hallucinogenics of Apocalypse Now and the green matter-of-factness of Platoon – and yet even beyond its harrowing message and unforgettable sights (D’Onofrio’s leering insanity, the rage etched on the face of the teenage sniper), it’s probably the most quotable war movie that has ever existed with everything from Hartman’s weapons grade verbal barrages, to the infamous “Me love you long time” entering the public lexicon with the ferocity of of the North Vietnamese staging their attacks in 1968.

Traumatising, harrowing and yet utterly enthralling in the most horrifying of ways, Full Metal Jacket proves that war can be hell even before you touch down into an active war zone, but anyone who has the audacity to say that the film noticeably drops in quality after the training segment is obviously an unorganized grab-asstic piece of amphibian shit. So to speak.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

Well hell froze over. I actually agree with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person