Hitchcock was always credited with being a master of suspense who was able to wring nerve-shattering tension with almost any scenario placed in front of him. However, away from the shower murders, bird attacks and that nasty bit of business involving Mount Rushmore, what many see to overlook is Hitch’s interest in the people all this horrible stuff was happening to.

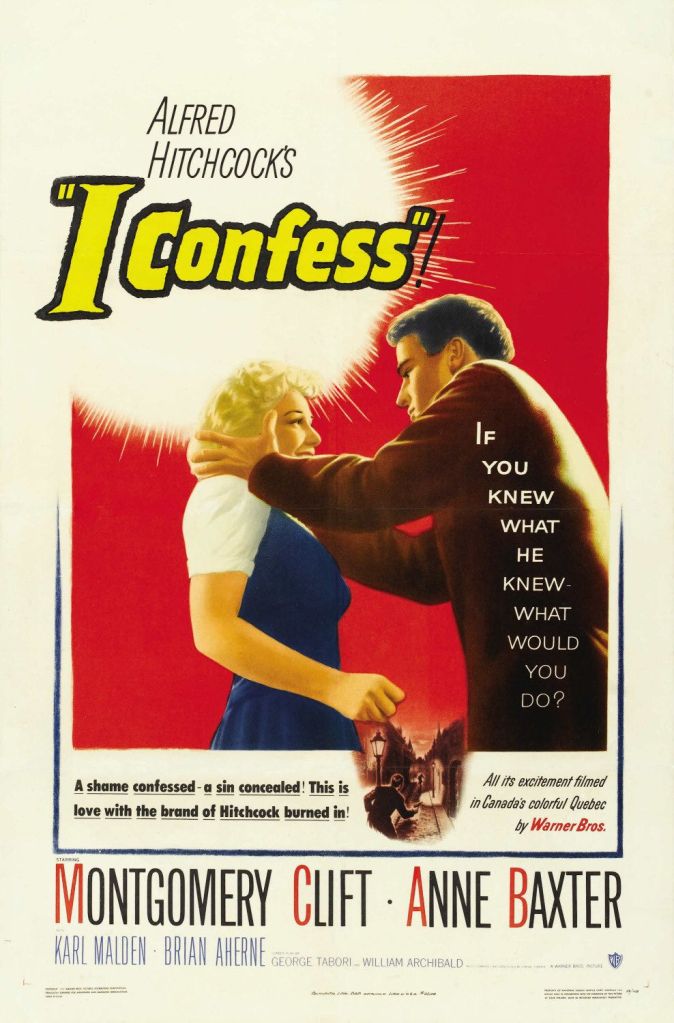

Never one to miss a chance to provide an antagonist with a gargantuan Achilles heel, the director seems to particularly enjoy tailoring a character’s weakness or vulnerability to a plot designed purely to exploit them. The most famous instance is obviously James Stewart’s titular ailment in Vertigo, but another intriguing example can be located in 1953s I Confess in which the legendarily mischievous director sought to make the very laws of priesthood a veritable venus fly trap in order to ensare our hero.

Devout Catholic priest, Father Logan, is a thoroughly decent man who tends to his flock in the town of Quebec City, but one evening, his German, immigrant caretaker, Otto Keller, stops by the church a requests that he gives a confession. Seated snuggly within the confessional, the sweaty, bug-eyed and very poor Otto starts to relate a disturbing tale which saw him try to rob the offices of shady lawyer, Villette, only to accidently be confronted by the man himself. After a brief struggle, Otto accidentally killed the man and escaped wearing a cassock to disguise his appearance, but uses his poor, overworked wife, Alma, as the reason he attempted the heinous deed in the first place.

However, despite Otto callously getting his murderous act off of his chest, he also has no intention of turning himself in despite Logan’s urging and the real catch is that the priest can’t reveal anything to the authorities if it’s told in confession. This would be awkward enough as it is, but unbeknownst to the scheming, weasley Otto, Logan had a few issues with Villette himself.

You see, a few years back, before Logan was a priest, he was in a relationship with loving blonde Ruth Grandfort, but they ultimately grew apart after the events of the Second World War and Ruth eventually married a future member of the Quebec legislature. However, a chance meeting between the two led to a misconception that – if it were revealed – would be scandalous to everyone involved. Enter Villette, who witnessed the two and decided to go into full, blackmail mode.

With an obvious motive and Otto setting him up every chance he gets, it seems that the determined Inspector Larrue will inevitably slap the cuffs on poor Logan sooner or later; but “all” the priest has to do to clear his name is break the rules of confession. What will win, the law or pure, undiluted faith?

While rather ungainly labelled by some as a “lesser” Hitchcock (I guess that’s what happens when your filmography contains numerous groundbreaking heavyweights), what the more quiet and meticulous I Confess lacks in obvious Hitchcockian flare, it more than makes up for in tea spilling, salacious gossip and people attempting not to crumble under the mounting stress. There’s no big mystery here as such as we (and our main character) are told precisely did the murderous deed within the first ten minutes of the movie, but the real aim of the game here is unraveling the tangled web of lies, deceit and blackmail on order to find out the events that’s bound the hapless Father Logan to a murder rap he can’t deny.

If he wasn’t bound by the rules of his faith, the movie would be barely fifteen minutes long, but in the hands of Hitch, the movie turns into a maze like mousetrap where a damning motive is only a convenient contrivance away.

Slightly disappointingly, Hitchcock puts lid on his more audacious use of the camera in this one, restraining his usual filmmaking tics to a walk-on cameo, the occasional creeping camera and a whole boatload buildings shot with Dutch angles – but it’s the actors and the labyrinthine back story that Hitch has his eye on the most. Donating the middle of the movie to one big info dumping flashback, it doesn’t exactly do wonders for the pace of the film, but it does enrich the story as the tendrils of the past ensnare our hero as a typically Hitchcockian victim of circumstance.

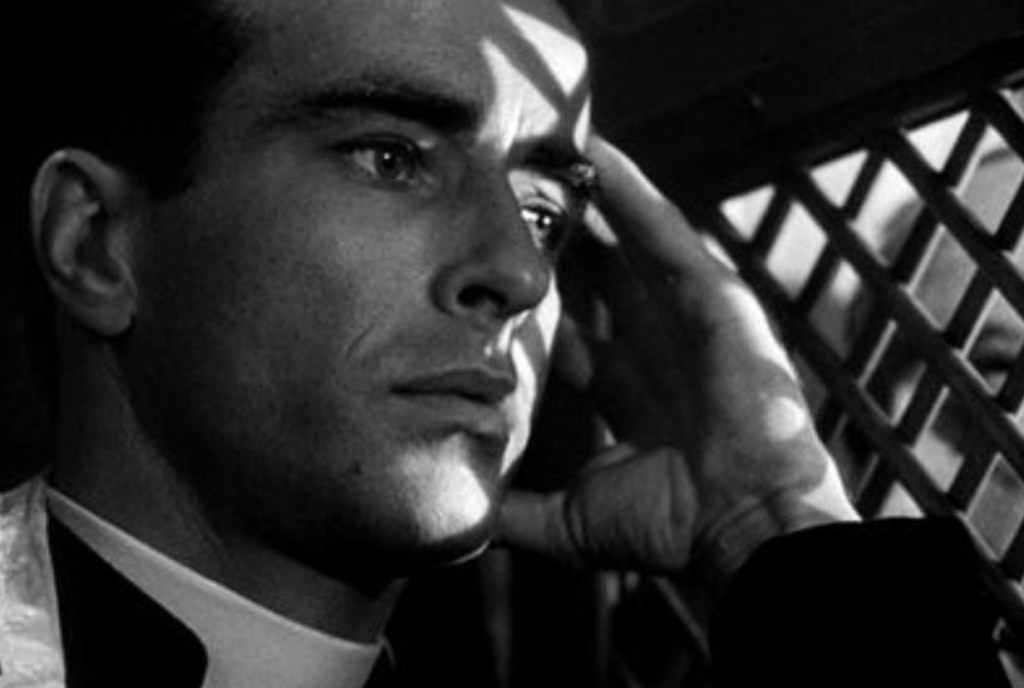

In the absence of camera based fireworks, it’s his human-shaped chess pieces that he focuses on more and the constantly worried looking brow of Montgomery Clift is well utilised by a simple man of the cloth who suddenly finds himself a little worm on a big, freaking hook as the lies and the scandal threaten to ruin every aspect of his very existence. Hitch has always been interested as the male character as sort of a damsel in distress and the predicament Logan finds himself, through no fault of his own, very much plays into the director’s themes of paranoia.

However, while Clift is a staunch and steadfast lead, it’s the supporting characters who garner far more interest, starting with Karl Malden’s straight arrow Inspector Larrue whose character helps the director visualise his love of police procedure with a keen, inquisitive mind – however you could argue that Malden, no matter how commanding, is merely something of an exposition machine compared to I Confess’ most interesting characters.

While Anne Baxter’s Ruth isn’t a villain in any way shape or form, the fact that she simply can’t let her love for Logan go after all these years is unwittingly the glue that makes all the evidence stick to the hapless priest like blood to a cassock. Not only this, but it’s her testimony that ultimately and accidently damns her former lover while she tirelessly and frantically works to give him an alibi – in fact, it’s probably one of Hitchcock’s jokes that the it’s careless blonde who causes more damage than the actual murder – but that’s Hitchcock for you.

Speaking of the murderer; the director obviously wasn’t interested in offering up a cold, calculating arch villain and instead gives us the perspiring hot mess that is O.E. Hasse’s Otto Keller, who must be one of the most panicky protagonists in all if 50s cinema. When he isn’t performing some of the most exaggerated and blatant gaslighting I’ve seen in years, his nervous, distrustful, squirrely nature constantly fucks up his own plans as he shows an impressive inability to even remotely remain calm.

Complaints of a disjointed tone or Hitchcock wrapping things up a bit too conveniently are valid, but I confess that I Confess had me hooked – if only for the spilling of secrets over the spilling of blood.

🌟🌟🌟