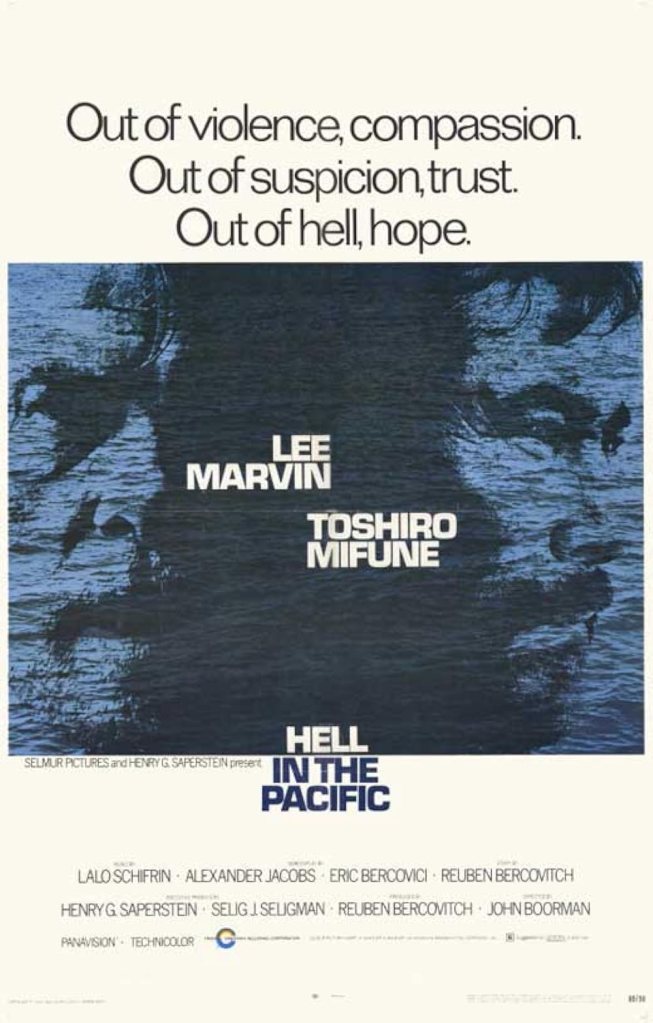

When it comes to celebrated filmmaker John Boorman tackling the Second World War, most people are drawn to Hope & Glory, his autobiographical take on the Blitz. However, rewind the clock back, past the weaponized insanity of Excalibur or Zardoz, or the traumatizing sodomy of peerless survival thriller, Deliverance and we find Hell In The Pacific, a tremendously off-beat anti-war war movie that the director used to follow up his unfeasibly cool crime flick, Point Blank.

Essentially the ultimate war film two hander, the whole gimmick is that the film only contains two servicemen; an American played by the crusty toughness of Lee Marvin, and a Japanese played by the mournful spirit of Kurosawa regular, Toshiro Mifune. As the two engage in a battle of wills with one another after being marooned on a deserted island in the Pacific, they veer from enemies, to allies and back again in what’s essentially the WWII edition of The Odd Couple.

Somewhere, on a deserted island in the middle of the Pacific, we find two servicemen who – thanks to the cruel machinations of the Second World War – have discovered that they are each stranded with their moral enemy. After discovering one another, their first thought is to square up and attack their foe, but while they stare each other down, both men lose their nerve when they picture what could happen if they were to come off second best in the fight and they both back down.

From there, the two men get to work basically haunting one another to get something aproximation an edge. The Japanese service man has the advantage because he has already made a camp and his managed to store a tidy amount of rain water to drink, so the American tries to find ways to covet the precious liquid by essentially being the sneakiest shit imaginable. But when his various attempts at obtaining something to drink via psychological warfare result in neither having anything to quench their thirst, things start to get desperate.

After yet another attempt at dueling to the death ends with the American passing out due to dehydration before they can even fight, yet more moral conundrums start tearing their head like a farcical Hydra. Unable to kill a passed out man in cold blood, the Japanese awkwardly takes the American hostage, binding him to a tree; but when he can’t bear the American’s accusatory gaze, the roles are soon reversed – but then the same thing happens to the American.

Stuck in a situation where neither man speaks the other’s language, they soon, finally start working together to build a raft in order to leave the island that’s imprisoned them, but can their truce hold after years of war have engrained such deep seated hostilities?

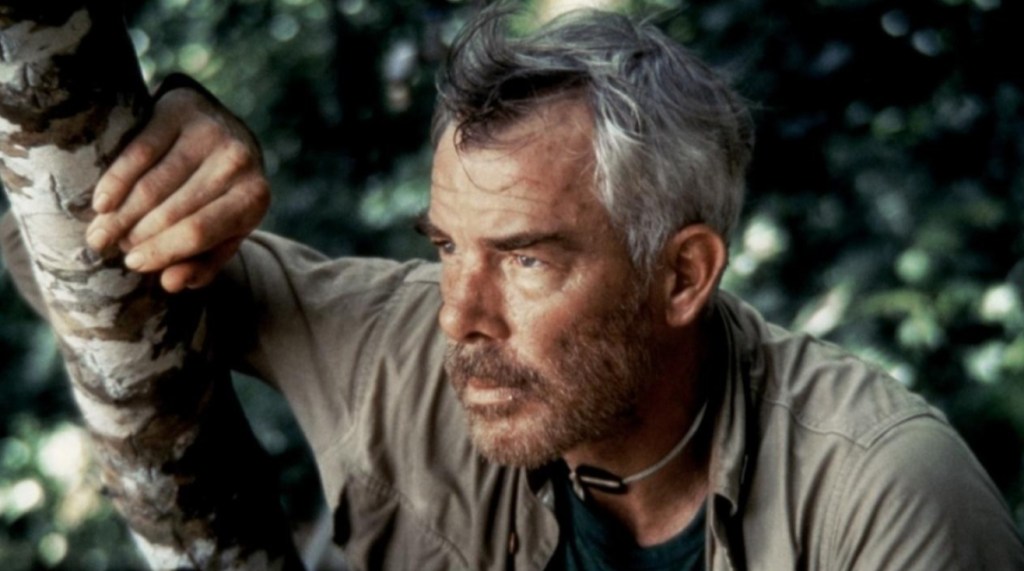

If the concept of Hell In The Pacific feels curiously familiar, chances are you’ve probably come across it while watching sci-fi oddity Enemy Mine, the opening scenes of Kong: Skull Island or some other film that dumps mortal enemies in the middle of nowhere and waits to see what happens next. Hot of Point Break, Boorman gives us a similarly bewildering adventure as he takes everything you think you know about a war film and proceeds to strip it down to it’s most minimal strand in order to give you the most overwhelming experience he can. For a start, both Marvin’s slightly entitled American and Mifune’s highly strung Japanese are barely given names – and if they are, they’re hardly used – and the language barrier is total, with no scenes of one learning even the basics of each other’s lingo whatever mirrored by the fact that even we, the audience, are denied subtitles for whenever Mifune speaks. We never see them actually wash up on the island and we aren’t shown the circumstances that caused them to be there – we aren’t even clued in to what type of people these guys are before they find themselves in tattered clothing under a burning son.

As a result, we just watch as Boorman strips everything from them in an effort to build something new – even their machismo is drained from their bodies in an early scene where both picture themselves losing a fight and then subsequently back down. It’s a brave and honest moment in a genre where, especially in the 50s and 60s, servicemen are usually portrayed as selflessly brave and usually infallible. However, Boorman is underlining the point that on this island, there are no good guys and bad, no heroes and villains, and throught the next hour or so, shows these two men trying to one-up one another like some fucked up episode of Tom & Jerry.

This is what takes up the bulk of the movie, a petty, deliberately clumsy power struggle between two guys, already frazzled by being marooned, who have nothing to lose and virtually nothing to gain. However, during their little power plays, the each manage, for a while, to capture the other and it’s here the character beats start to push through.

Lee Marvin’s American, the noticably more arrogant of the two, is more concerned with getting the Japanese’s water than trying to get some of his own, while Toshiro Mifune’s character is mired in keeping his honor than de-escalating the situation, easily rising to Marvin’s trucks and taunts. Both men are, unsurprisingly, excellent, but there is a feeling that Boorman is maybe making his point a bit too emphatically as the near silence save for the soothing splashing of the tide and the relaxing tweeting of birds makes it incredibly easy to zone out and lose track of what’s going on.

If you’re zeroed in on the film, with no distractions, then you get a painstakingly rendered relationship that sees any suspicion gradually eroded down in micro expressions and subtle gestures, but be warned, if you have anything else within reach, a book, a phone, anything, the temptation to skim is high, especially when you consider that the film doesn’t really gain narrative traction until the two finally start working together.

It’s with the building of the raft and the eventual discovery of an abandoned base on another island that Boorman finally makes his point.

Forging a bond with their escape attempt, it seems that all the two need to backside into war-programmed mistrust and hatred is the slightest taste of civilisation is enough to fire up conflict. Marvin gets drunk and starts banging on about religion, Mifune gets drunk and reads a magazine that has photos of Japanese prisoners and that’s enough to undo everything they’ve built to.

Whether you’ve watched Boorman’s intended version, where the two angrily walk away from one another, or the abrupt and unintentionally silly studio ending, which sees the glaring pair suddenly obliterated by a bomb, Hell In The Pacific is both a rewarding and frustrating watch, that fittingly has the two go to war inside the tropical island of your emotions.

🌟🌟🌟