If anyone understood the need for high adventure, it was Walt Disney. Obviously, not every timeless, fantasy epic he oversaw was rendered in lush, groundbreaking animation as others, such as Pete’s Dragon and Mary Poppins and Bedknobs And Broomsticks were presented with flesh and blood actors and actual sets. Possibly one of the most epic of these was their no-expence-spared adaptation of Jules Verne’s science fiction adventure flick, 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea that not only was the first live action Disney film to be shot in Cinemascope, but is still regarded as the definitive go-to version of the famous story, beating out all others.

So batten down the hatches, ready the ballast and join James Mason, Kirk Douglas, Peter Lorre and an amorous pet sea lion named Esmeralda as we dive to the titular depth, engage in watery daring do and inadvertently help give birth to steampunk as we embark on the adventure to end all adventures.

During the year of 1868, rumours are abound of a deadly sea monster whose rampage has been sinking ships all over the Pacific Ocean, and so Professor Aronnax – with the help of his assistant, Conseil – has decided to investigate with the aid of a U.S. Navy frigate. Initially, the search proves fruitless and soon the crew, along with bolshie, tag along harpooner, Ned Land, begin to grow restless, but after months of searching, the monster is eventually spotted.

However, in the wake of the confrontation, two things become apparent: firstly, this monster is certainly no slouch when it comes to nautical warfare and secondly, this sea monster is no monster all, but but instead is a marvelous submersible vehicle named the Nautilus that is centuries ahead of its time. Finding themselves onboard, Aronnax, Conseil and Ned are soon introduced to the captain of this mind blowing vessel, the embittered, vengeful Captain Nemo, whose hatred of humanity has driven him in his quest to wage war on mankind. Of course, Ned and Conseil immediately have the not so good Captain pegged as being a few tentacles short of an octopus, but Aronnax, while wary of Nemo’s gargantuan, misanthropic nature, sees the man as someone to study and learn from so the world can discover and benefit from the technological secrets of the Nautilus.

Of course, Nemo finds this concept as distasteful as Ned finds the milk from a sperm whale (one of Nemo’s ocean derived delicacies) but as he continues his destructive mission, both Ned and Conseil plan to either escape or mutiny, whichever seems most likely.

Aronnax seems adamant that he can pull the Captain back from the dark side, but even if he can will the world make him regret ever finding Nemo?

If I’m being totally honest, I often find the live action classic Disney stuff a little too fanciful for my tastes as the rather broad acting that comes with it and their insistence on chucking in at least one full song in there whether the movie requires it or not only really excels in the virtually flawless Mary Poppins. However, I have to admit, watching Richard Fleischer’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea for the first time as an adult was not only a stirring experience, it’s something of a vital link in the crafting if the modern blockbuster. For a start, the way that the movie visualises Verne’s book is a masterclass on how to adapt sci-fi; take the Nautilus, for example – surely one of the most iconic designs for a cinematic submersible that’s ever existed that finds that rare sweet spot between something that’s legitimately cool, excitingly fanciful and weirdly feasible all at the same time. With its memorable fins, countless rivets and green, eye-like domes, it’s said that the design helped immensely in the rise of the design ethic known as steampunk and is almost a character in of itself.

Of course, a ship is only good as its crew, and James Mason’s Nemo certainly scores in making the Nautilus as seaworthy as it can be as his usual shtick of seeming trying to be the worlds most civilised man butts nicely uo against the fact that for all his genius, Nemo’s sanity is actually as transparent as a bloody jellyfish. However, matching Mason’s wavering mask of calm with an utterly unrestrained show of camp machismo is the butt-chinned human dynamo the world knew as Kirk Douglas. The actor’s continuous desire to prove his virility on screen is legendary, but inbetween him constantly running around the place, taking of his shirt every ten minutes like a chippendale Popeye and flirting with Nemo’s pet sea lion, he’s a welcome switch from the the other two leads. It’s not that Paul Lukas’ straight-laced Aronnax or Lorre’s typically lizard-like Conseil is bad (and it’s genuinely nice to see the latter in heroic, comedic form), but trapped between the maelstrom of Mason’s dignified insanity and the sight of Douglas randomly launching into a sea shanty about how many women he’s banged, they don’t have that much of a chance to register.

Also threatening to dwarf any of the slower swimmers in the acting department is Fleischer’s production design which, even to this day is worth mentioning as a high point on adventure cinema. Walt’s decision to have the director shoot in Cinemascope is nothing less than inspired, causing the blues of the ocean pop just as much as the red stripes of Douglas’ regularly discarded shirt and the detail in Nemo’s resplendent quarters is nothing short of delicious.

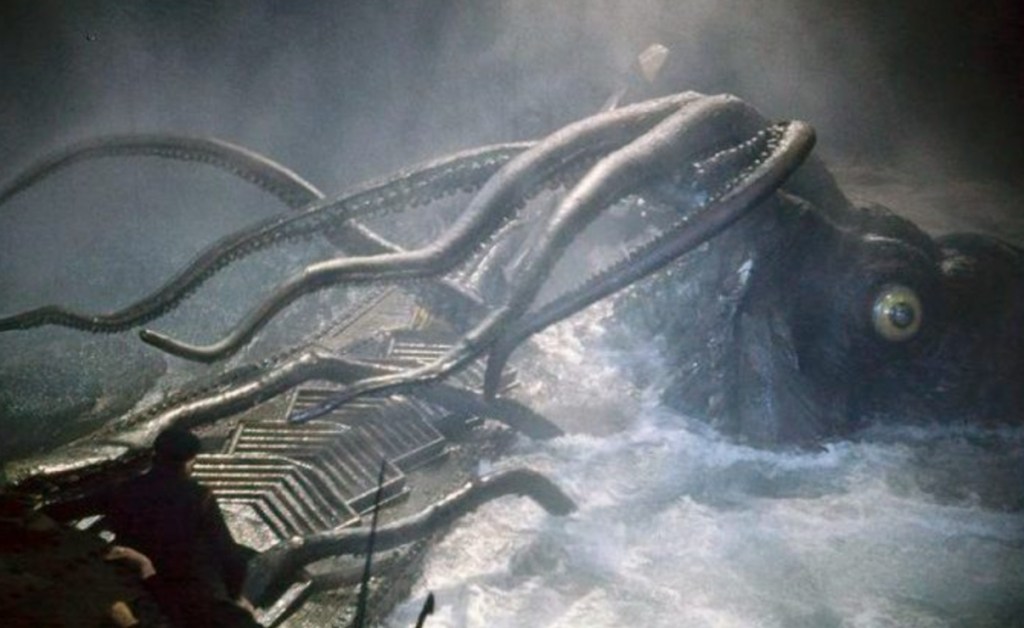

While the fact that the bulk of the adventure is taken up with our three leads languishing around the Nautilus as Nemo doubles down on his anti-humanity manifesto means that modern audiences may find things a little slow going, you can’t help but notice that there’s more than few scenes here that directly inspire moments from more modern movies. The reaction to Nemo’s sea-harvested feast isn’t that different to the banquet sequence from Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom and moments that sees Nemo gives it the large one on his huge, gothic organ (steady now) or Ned fleeing from cannibals are strongly reminiscent of Pirates Of The Caribbean. With that being said, you can’t compare 20,000 Leagues and Pirates without discussing the former’s genuinely kickass giant squid attack, which, for all its grasping rubber tentacles and snapping beaks, holds up remarkably well mainly thanks to it being an entirely practical effect.

The usual Disney sense of bounciness is in full effect which may diffuse some of the tension that the film could have had (none of our three good guys ever remotely fell like they’re in any, genuine danger), but there’s no disputing that House of Mouse’s dedication to scale, grandeur and high adventure was second to none – and if nothing else, the cinematography and the sight of Douglas strumming a homemade ukulele fashioned from a fish spine and a turtleshell help through chopier waters.

🌟🌟🌟🌟