As time steadily ticks on, it often mean that certain opinions or takes on history tend to fall out of favour when more modern and more balanced views take hold. That often means that when it comes to the rather delicate matter of war films, some movies simply take an old fashioned stance that unavoidably puts it at odds with undated sensibilities. Not World War II of course, heavens no, the Nazis will always be arguably the genre’s greatest, most indisputable villains and that will probably never change, but as we shift our focus further back through time, things tend to get noticably more complicated.

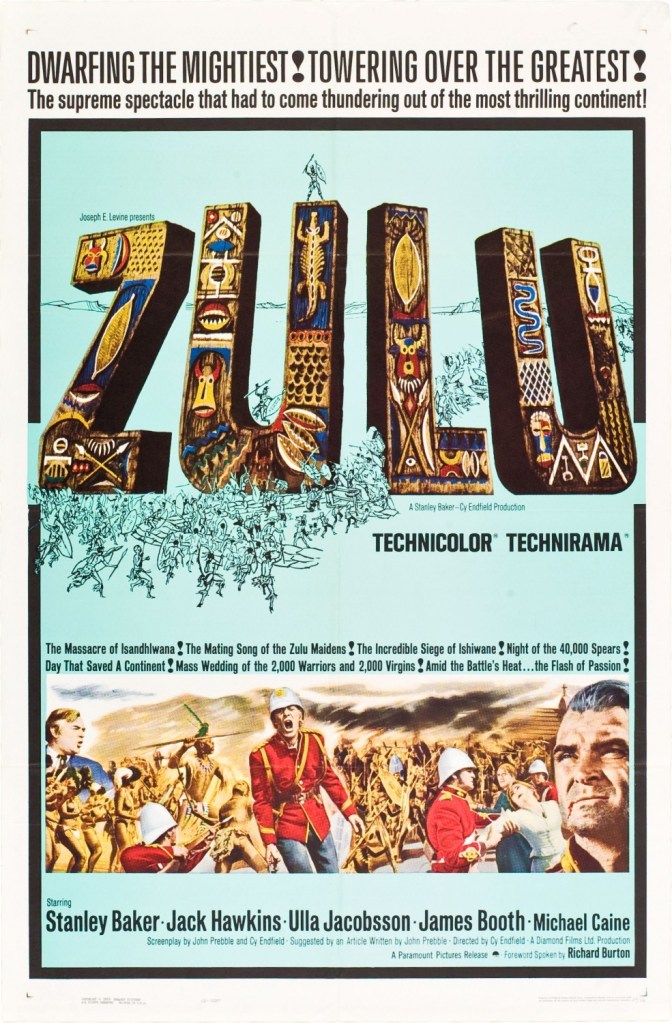

Take Zulu for example, a staple of holiday dad-viewing that arguably rivals the likes of The Great Escape, The Godfather or The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, but while this movie gave us epic battle sequences and a breakthrough role for none other than Michael Caine, there’s rather a sizable stigma there thanks to the thorny subject of British colonialism.

It’s January 1879 and word has gotten out that the Zulu armies have absolutely crushed a British column of soldiers numbering 1,300 strong at Isasndlwana. This news is startling to anyone to anyone that hears it but it’s extra worrying to missionary Otto Witt and his daughter who happen to be watching a mass marriage ceremony within the tribe at the time. Understandably panicked, they flee via coach to the remote outpost of Rorke’s Drift in Natal to not only warn them, but try and extract the sick and wounded that are recovering in their barracks before the 4,000 strong Zulu horde arrives.

However, to Otto’s horror, they are met by Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers, who promptly takes charge and girds the outpost for the fight of their life, despite the fact that there are only 150 men stationed there and 30 of those make up the sick and wounded. As he starts making some incredibly difficult decisions under the somewhat sardonic eye of Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, he decrees that the sick have to stay and fight with the rest of the men and start trying to fortify the outpost with bags of grain.

While there are a few that disagree with his decision (an apoplectic Otto being one of them), someone who really doesn’t appreciate it is Private Henry Hook who has been faking various injuries to con his way out of active duty and now finds himself stuck in the middle of a battle ground.

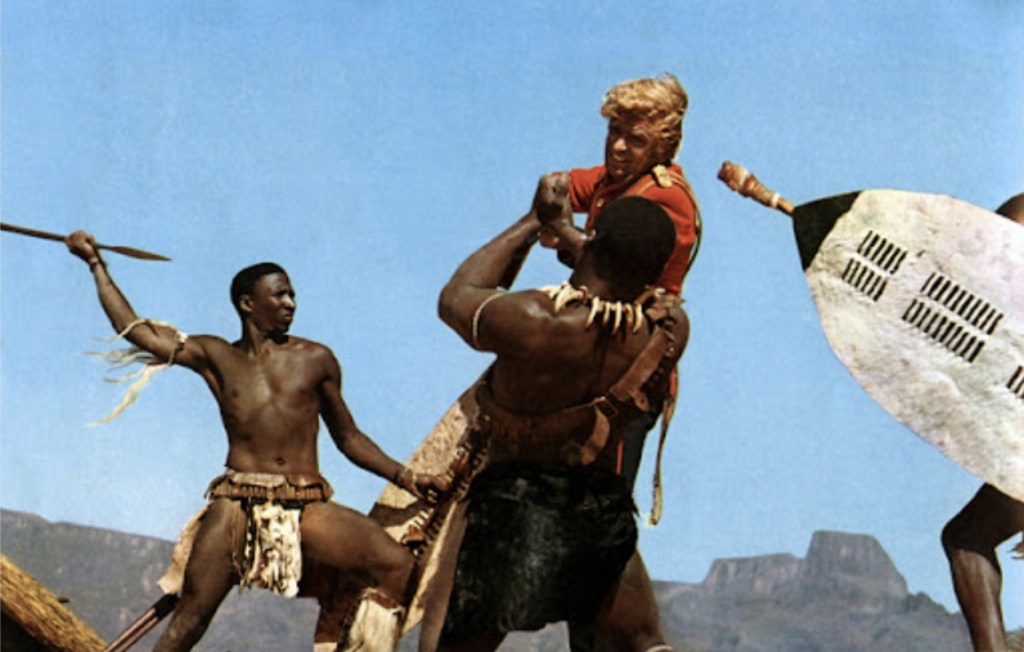

Soon the immense amount of Zulus arrive looking to roll over the outpost like a tidal wave armed with spears and it’s down to the meager force to try and fight them off with no hope of rescue.

As wave after wave of warriors hurl themselves at the outpost, the fight is joined in earnest but can such a small number of men manage to hold back such an overwhelming force?

OK, so even though Cy Endfeild’s Zulu does the best it can (for 1964) to bend over backwards and try to paint the fighting men of the Zulu armies as intelligent, measured warriors who blatently understand the concepts of honor and who have a pretty intricate battle plan, there’s always going to be issues with Zulu simply because of the reason the British are there in the first place. Yep, celebrating colonialism certainly isn’t as acceptable as it used to be and anyone who understandably can’t or won’t put that aside to appreciate the movie in a moral vacuum simply isn’t going to care about any of the many plus points the movie has. Yes, the very nature of the film is to portray a race war where killing as many people of a diffrent colour than you is a plus if you want to survive, but while the 60s politics paint the British entirely within their rights to be doing what they’re doing, I’ve never truly believed that’s what the film is supposed about.

When the British presence in Southern Africa is merely taken as a setting, the film is more preoccupied with setting up the notion of a vastly inferior group bracing themselves for an onslaught from a vastly superior force and everything that comes with in. In fact, the first half of Zulu actually feels more like that of a disaster movie as we focus on individual clumps of soldiers as the pressure steadily mounts as that famous stiff upper lip is steadily tested. Taking point is Stanley Baker’s John Chard who finds he has the thankless task of trying to make impossible decisions to defend the outpost as he is propped soley up by the impossible demands of duty that simply won’t allow him to announce a retreat – not that it would help because it’s far too late. Certainly not helping much is the fact that Michael Caine’s upstart Lieutenant is seemingly always standing roughly ten feet away ready to offer a question, notes, or a withering disagreement, but even Bromhead has plenty more decoram than Otto the missionary whose constant meltdowns help make the dread settle all the heavier.

Elsewhere, we also get to see how the expectation of certain death effects the lower ranks and there’s a certain amount of fiendish pleasure watching James Booth be a nihilistic pain in the arse as he desperately tries to skive out of absolutely anything he can.

Rounding things out are Patrick Magee’s understandably stressed doctor and a couple of wistful Welshmen belting out a tune to calm their spirits. But with all the preamble out of the way, it’s time for the battle to start and Zulu makes a big shift into organised chaos as it painstakingly lays out what it means to essentially fight for your life for hours on end. The Zulus battle plan is to keep testing all the different sides of the outpost, often at the expense of many lives, to find any kind of weakness they can. While they do this, the men inside desperately try to stem the tide with rifles and bayonets, but if it doesn’t seem like a particular assault is working, they’ll withdraw, take a minute and then have their warriors charge in from another side. While the battles are obviously not shot in real time (the film ain’t that long), Endfield makes us feel the battles as you can practically sense the fatigue and the heat as each attack brings the enemy ever further into the outpost. It’s a technique that’s picked up some pretty sweet homages over the years, after all, where would the truly magnificent Whiskey Outpost sequence from Starship Troopers be without Zulu.

However, while it’s pretty acceptable to have unrepentant colonisers blow the shit out of an endless mass of murder bugs, you might not agree which how Zulu treats its titular warriors. While the tribesmen are only portrayed as mindless brutes in the same way most of the background English are fairly faceless, the film does try to give a nod to their culture, but that doesn’t mean any of the Zulus a garnished with anything even remotely resembling character or an arc. Further still, the final scenes where they sing the praises of the survivors as worthy adversaries may big up the bravery and grit of the soldiers, but it’s a little hollow when you consider why the British were there in the first place.

Whatever your feelings about the period and the nature of colonialism in regards to the film, you still have to admit as an example of tense, prolonged warfare recreated on film, Zulu contains more than its fair share of memorable moments. Thousands of them…

🌟🌟🌟🌟