For decades, the modern werewolf genre was held in the vice like grip of two of the finest werewolf movies to ever howl at the moon: An American Werewolf In London and The Howling. There were incredibly acceptable also-rans, of course; Neil Jordan’s The Company Of Wolves added a fantastic fairytale twist to proceeding, but technically it was more Brothers Grimm than Lawrence Talbot and so fans of fur and fangs waited patiently for practically the entirety of the 90s until the genre produced something that truly shot for the moon.

Well, bounding in from Canada to put the “gory” into “allegory” was Ginger Snaps, a movie that took all the unwanted hair, changing bodies and inconvenient blood loss of puberty and linked it to the effects of lycanthropy. Not only that but it took a massive dollop of millennial angst and teenage rage to not only give it the edge and acerbic wit of something like Heathers, but it finally did the werewolf genre right in a way that hadn’t been done in years.

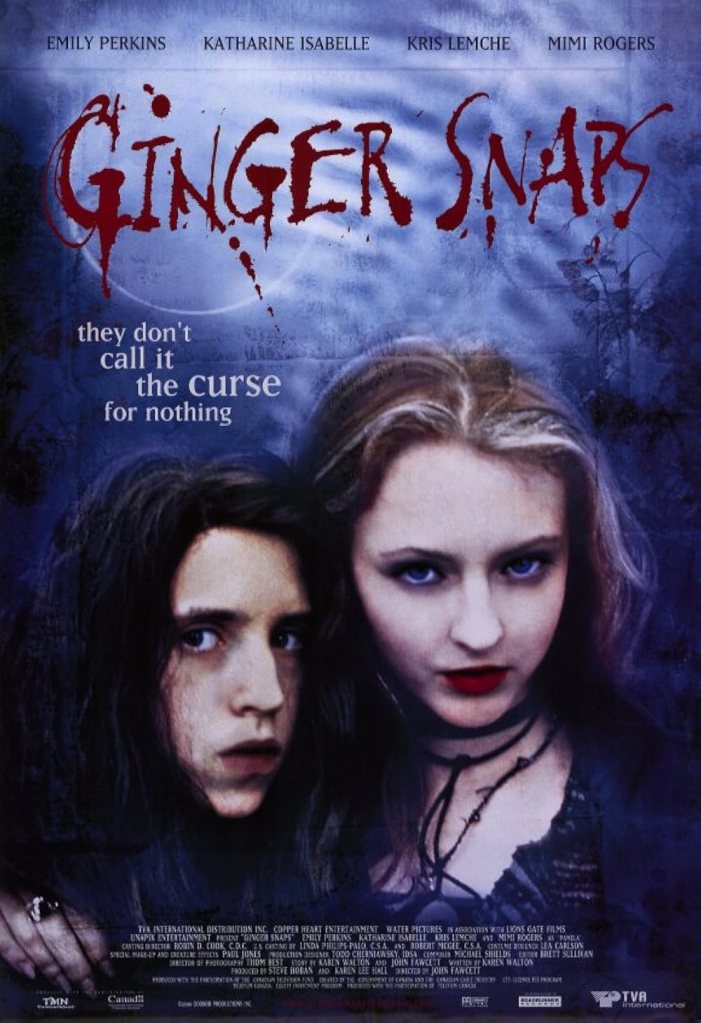

Meet Ginger and Bridget Fitzgerald, two awkward, outcast sisters who have dedicated their mid-teens to leaning in hard into their weirdo status and fascination with death to try and freak out as many fellow high-school students as they can with their sallow-eyed, gothic interests. However, while their morbid school projects horrify their teachers and confuse their parents, the Fitzgerald sisters have an unbreakable bond forged by an attitude of them against the world. But this is shakened when the sixteen year old Ginger finally gets her belated, first period which delights their mother but freaks out the girls. Meanwhile the quiet suburb where they live is currently under siege by a mystery animal dubbed the Beast of Bailey Downs that’s been feasting and gorging itself on the neighbourhood dogs.

After a run in with popular girl Trish Sinclair, the sisters decide to pull a prank and head out one night to steal her dog and blame it on the beast, but it horribly backfires when the actual creature show up and savages Ginger brutally. However, in a bizarre turn of good(ish) luck, the monstrous wolf creature is taken out of the picture after being obliterated by a passing van (who needs silver bullets, eh?) and it seems that Ginger’s grevious injuries seem to start healing almost immediately to the point that they are mostly nasty scars by morning.

Ginger seems willing to put the entire ordeal behind her and forget about it, but Bridget is far more suspicious, especially when all the clues point to an unbelievable truth: werewolf. However, when the older sister starts experiencing gradual changes to her body that can’t be simply explained by her inexorable blossom into womanhood. As Ginger gets progressively more feral and wayward the more lycanthropy takes hold, Bridget teams up with the local drug dealer to try and whip up a cure before the teen’s bloodlust becomes impossible to resist.

To be fair, the whole puberty-disguised-as-classic-horror-convention is something of an overused trope in this day and age as virtually every single monster on the block has had a crack at reinventing itself through the prism of periods, cramps and tampons, but back in 2000, Ginger Snaps managed to be something of a revelation. Of course, Buffy The Vampire did it first, but the world of Buffy Summers, Vampires and High School obviously came with the restrictions that went hand in hand with television at the time, giving Karen Walton’s fang-sharp screenplay and John Fawcett’s intelligent direction almost a clear playing field to use to their advantage. A huge advantage – possibly it’s greatest – is the script, that not only honors the first commandment of any teen movie that demands you don’t talk down to your audience and have your young leads speak in a way that’s both natural and hugely witty but it tackles the more “feminine” aspects of the story admirably head on.

Thanks to David Cronenberg, Canada is sort of the official home of body horror and you can’t get much more body horror than some poor wretch going through the trauma of puberty, so Ginger Snaps fully recognises that while the journey to womanhood should be a wonderous time, the reality is that it’s often a period (pun not intended) that causes feeling of awkwardness, shame and immense discomfort as your body literally rebels against you. While there are numerous other parallels to be made between the minefield of teen life and transforming into a flesh ripping beast under the light of a full moon such as Ginger’s latent sexuality rushing to the surface the moment males start noticing her and a growing rift between siblings as more adult pursuits drive a wedge between any childhood pacts (‘Out by sixteen or dead in the scene” is their self destructive mantra) the film also touches on such subjects as self harm, drug use and teen suicide with the same sardonic, wicked, humour as everything else.

The other main aspect of Ginger Snaps’ recipe comes in the form of both Katherine Isabelle’s Ginger and Emily Perkins’ who both inhabit their roles completely. Isabelle relishes playing the isolated teen who becomes a horny predator thanks to her full moon mauling, but her panicked outrage at the early stages of her lycanthropy (that includes growing a fucking tail no less) soon gives way as she gradually loses her humanity and patience with the insipid males in her orbit. In comparison, the mousey and sullen Perkins switches into teen Van Helsing mode as she teams up with Kris Lemche’s game weed grower to try and scientifically crack the code of lycanthropy that doesn’t suddenly jump the shark and she sells her fear for a sister who is murderously out of control beautifully. Of course, while the two young leads do magnificently, an extra nod has to go to Mimi Rogers’ perpetually cheerful matriarch who soon reveals the darkly hilarious lengths she’d go to to protect her girls.

However, while all the spot on teen drama gives the werewolf genre a fantastic new coat of fur, the foundations of Ginger Snaps actually hue incredibly close to the classic Wolf Man films of yore. Werewolf movies, as a rule, need to ultimately be tragic affairs that tear families apart – even the Lon Chaney Jr. one required him to be killed by a loved one – and the entire film carries an underlying somber tone that this can’t possibly end on a happy note.

Some might complain that the final act goes too far into traditional horror territory with a cat and mouse stalkathon with a fully transformed Ginger, but I would argue that even then, the film manages to maintain its memorable attitude by delivering a truly interesting creature design that looks more feline than your average moon howler. If there is such a thing as Mount Rushmore of modern werewolf movies, I genuinely believe that Ginger Snaps fully deserves to be up there, head and haunches alongside the likes of American Werewolf and The Howling.

Puberty sucks. Ginger Snaps rules.

🌟🌟🌟🌟