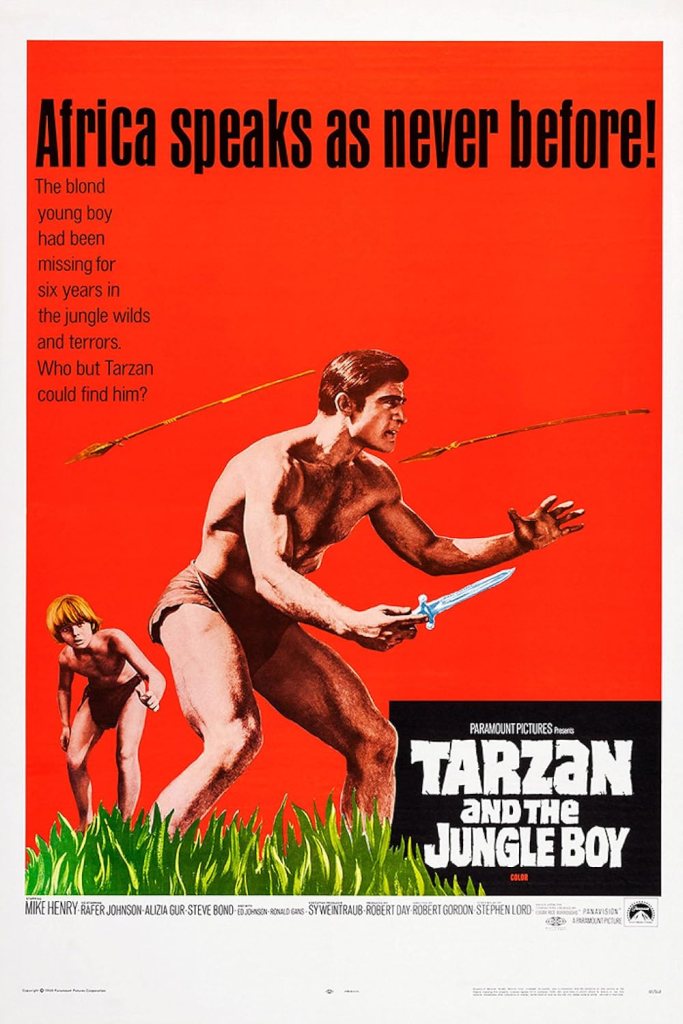

As Tarzan emerges from the sweltering jungle for his latest adventure, there’s almost no sense that the official run of movies was about to slip into a blight of jungle fever that would last over a decade. The twenty eighth film in a franchise that technically started in 1932 (although there were also silent movies based on Edgar Rice Burroughs eponymous tree hugger) Tarzan And The Jungle Boy not only brought Greystoke’s impressive cinematic run to a screetching halt, but it was also the final appearance of Mike Henry bulging biceps in the title role.

So, what finally brought Tarzan down when racially dubious headhunters, moustache twirling Nazis, rubber crocodiles and stock footage of attacking lions had failed to do the job for the better part of thirty six years? Well, I’m not a hundred percent certain, but the rise of a certain gadget known as the television set probably had something to do with it.

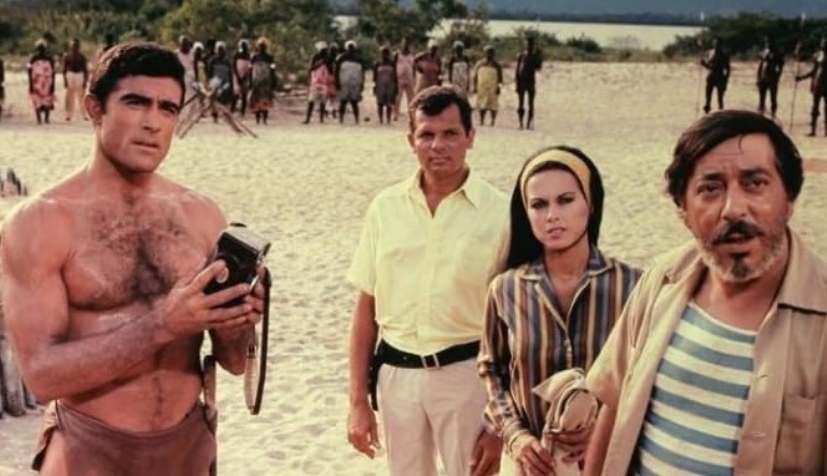

After a world tour that had seen Tarzan righting wrongs over the last couple of years in such places as Brazil, Mexico and India, we finally find our jungle lord back on his home turf in Africa. However, even though he’s not jet setting around the globe in order to punch out animals from other countries, there’s still plenty of problems to keep the loinclothed one busy and his latest gig literally falls out of the sky in the form of parachuting photojournalist named Myrna.

It seems that her and her deep voiced colleague, Ken, have arrived to seek his help in finding Erik Brunik, a thirteen year old boy who has been lost in the jungle since he was seven years-old. Now, while the thought of a prepubesent child managing to survive in the African jungle for seven years may seem as far-fetched as your average Fast & Furious sequel, Tarzan has something of a past experience with kids surviving in deadly surroundings (just check his autobiography), so the tragic tale of Erik galvanised him into sinew-stretching action.

However, there’s a major issue with the rescue as it falls within the land populated by a particularly strict tribe who is currently undergoing a spot of reshuffling when it somes to their seat of power. As the tribe’s chief slowly succumbs to age, his two, strapping sons, the noble Buhara and the conniving Nagambi battle it out for the right to rule, but when Tarzan thwarts a spot of cheating-cum-attempted homicide, Nagambi vows to bit only kill his victorious brother, but also kill Erik the jungle boy simply to get back a Tarzan for sticking his righteous nose in.

Soon everyone is wandering around the jungle in the act of searching for someone or other, but inevitably the power struggle between the two brothers ensnares all involved and Tarzan once again has to clean up another mess

Much like other, long running franchises, by the 60s, Tarzan was feeling the pinch thanks to the rise in popularity of television. As more and more households got the game changing invention in their homes as it became more affordable, producer Sy Weintraub reasoned that having the ape man swing over from the big screen to the small screen would be more cost effective. In fact, Mike Henry was even tapped to remain under the loin cloth once the shift happened, but it’s here that we find that some of the goodwill collapses after the Tarzan actor had something of a sizable disagreement with a fellow cast member.

Now, an argument with a fellow thespian is one thing, but when you consider that the beef was which the chimpanzee who played Cheeta, you can imagine how bad things could have got. Not only was Henry bitten on the jaw by the movie’s comic relief, but he subsequently tried to sue Weintraub citing exhaustion and unsafe working conditions, which kind of makes sense when you consider that he’d managed to film all three of his Tarzan adventures before the first even managed to get into theatres. While it’s debatable how much all of this contributed to Tarzan being absent from the silver screen for so long, it certainly proved to be Henry’s last outing and once the character made his debut on the tube (now played by Ron Ely), the writing was on the wall.

The reason I’ve gone through this random history lesson is because for all the issues going on, Tarzan And The Jungle Boy is such a standard, basic, typical Tarzan movie, it’s a real shame that the film couldn’t close out such an impressive run of sequels with an entry that stood out a bit more – but on the other hand, I suppose it’s nice that the original franchise finished out its run back in Tarzan’s “native” Africa after zipping him all over the world for the past few years.

Aside from that, it’s all standard Greystoke stuff – there’s the comedy chimp getting up to his typical shenanigans (not including biting someone’s face, of course), outsiders arriving to offer Tarzan a mission, yet another replacement for the character of Boy and some iffy internal politics concerning a local tribe. The problems that the script tries shoehorn in so many of these connecting stories, it actually forgets to do much with its frequently oily lead.

It’s odd, because there’s actually some real potential here to elevate things a little beyond the usual escapist adventure as Tarzan almost literally has to confront a younger version of himself who has almost the exact same origin story. While the scenes of Tarzan chilling and bonding with Erik while both of them lounge about, wearing nothing but loin cloths may not have aged particularly well (it’s admittedly a little creepy), it’s a perfect opportunity to link the character back to his roots – but unfortunately the two don’t even meet until around twenty minutes from the end if the film.

Elsewhere, while I always tend to brace myself whenever the franchise starts to dig into plotlines featuring African tribes as it’s usually a hotbed for some racially uncomfortable portrayals, the battle between Buhara and Nagambi to rule their tribe is actually the best thing here as it takes so many twists and turns. However, between this and the search for Erik, Tarzan himself has almost nothing to do except chastise Aliza Gur’s ineffectual photojournalist, jog randomly through the jungle, or simply stand and watch while others do the heavy lifting. Considering that Henry’s Tarzan was always more effective when he’s actually in action – he still looks the part, but his delivery still as inanimate as a zebra carcass – having him watching from the sidelines while the two brothers fight for their tribe just seems a little odd and certainly isn’t the send off you’d hope for the legendary adventurer.

Still, as bog standard adventures for the king of the swingers go, it’s certainly not unwatchable, but it’s just weird watching one of literature’s great adventures become a relative man of inaction.

🌟🌟